A beginner's experience with TLAPS (The TLA+ Proof System)

- 14 mins- 1. Pre-requisite Knowlege and Resources

- 2. Motivation

- 3. Getting Started

- 4. The “Hello World” of TLAPS

- 5. Proving Transitive More-Than relationships

- 6. Proving Some Square Root Stuff: Using Operators and Structured Proofs

- 7. Dividing Linear Combinations

- 8. Conclusions

1. Pre-requisite Knowlege and Resources

- My initial post on Learning TLA+ - to understand the difference between TLA+/PlusCal/TLC (finite state checking) and TLAPS (general proofs)

- A basic understanding of TLA+ syntax. Even without this knowledge, perhaps the syntax in this post will be self-explanatory.

2. Motivation

The resources in my first TLA+ post were extremely useful to me in understanding the TLA+/TLAPS syntax and semantics, but I found each source individually to be either too focused on specific examples or too general. This post will focus on interleaving examples of increasing complexity with the syntactical constructs in the language.

3. Getting Started

3.1. Pre-Requisites

- TLA+ Toolbox is installed

- TLAPS is installed from binaries or source - does not come with the Toolbox.

3.2. Writing proofs in the TLA+ Toolbox

- Open a new specification or .tla file in the TLA+ Toolbox

- To prevent complaints from the PlusCal translator, keep an empty algorithm block in the file

(* --algorithm proof begin skip; end algorithm; *) - Alternatively, you can just add the theorems and proofs to an existing .tla file with standard TLA+/PlusCal code, these two systems co-exist and actually benefit from each other

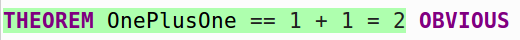

4. The “Hello World” of TLAPS

We’re going to force TLAPS to prove 1 + 1 = 2, a real test of its abilities.

I find there are two classes of constructs when using TLAPS:

- Theorems (Describing what needs to be proved)

- Proofs (Actually proving the active theorem)

For TLAPS, the theorem would be written as:

THEOREM OnePlusOne == 1 + 1 = 2

Here, the proof is obvious, since it follows from standard mathematical knowledge. So, the proof is written as:

PROOF OBVIOUS

Putting both theorem and proof together, we get:

THEOREM OnePlusOne == 1 + 1 = 2

PROOF

OBVIOUS

What caused some confusion during the process of learning TLAPS was that:

- The word “PROOF” is optional

- Newlines are usually ignored

So the proof above is equivalent to

THEOREM OnePlusOne == 1 + 1 = 2 OBVIOUS

and

THEOREM OnePlusOne ==

1 + 1 = 2

PROOF OBVIOUS

etc.

4.1. Running these proofs

In the TLA+ Toolbox: Use Ctrl+G Ctrl+G to prove a particular step of a theorem. The theorem and its associated steps turn green if the proof backends prove the theorem with the proof that’s been given.

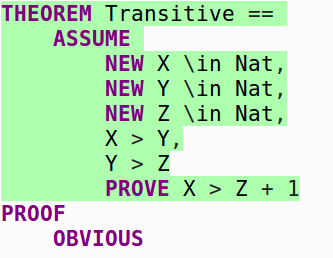

5. Proving Transitive More-Than relationships

We want to prove that if X > Y and Y > Z then X > Z + 1.

THEOREM Transitive ==

ASSUME

NEW X \in Nat,

NEW Y \in Nat,

NEW Z \in Nat,

X > Y,

Y > Z

PROVE X > Z + 1

Here, we declare 3 new identifiers (X, Y, and Z) and declare their domain to be the Natural numbers (this requires an EXTENDS Naturals at the top of the .tla file)

Is this an obvious proof? In general, I try to use PROOF OBVIOUS every time just in case TLAPS can figure out the proof without any additional information. Here, the set of facts available to prove X > Z + 1 is X \in Nat, Y \in Nat, Z \in Nat, X > Y, Y > Z. So is TLAPS able to figure this out without any more information?

Looks like it. Adding PROOF OBVIOUS to complete the proof is sufficient for TLAPS in this case. Let’s move on to a slightly more complex example.

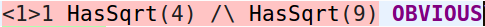

6. Proving Some Square Root Stuff: Using Operators and Structured Proofs

We want to prove that 4 and 9 both have a square root. Pretty easy, but we also want to define a generic operator to check if some variable has a square root. Our implementation will be:

HasSqrt(Y) == \E k \in 1..Y : k * k = Y

Or “Y has a square root if there exists a value k in the range 1 to Y such that k * k is Y”.

Let’s state our theorem:

THEOREM TheseHaveSqrt ==

ASSUME

NEW X \in {4, 9}

PROVE HasSqrt(X)

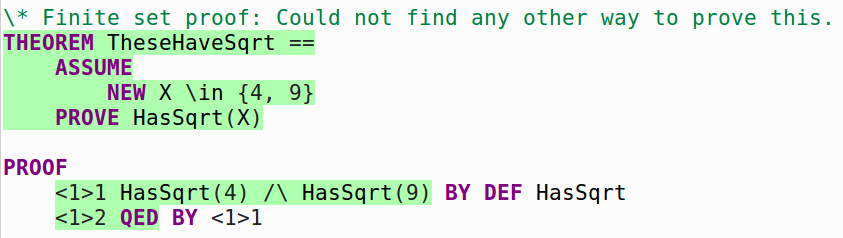

So our proof here could be stated in one step, but it’s a good time to introduce the idea of structured proofs. These are multi-line proofs that can have step numbers and refer to each other. Each step is its own proof obligation, i.e. something that has to be proven as well, and proofs can be nested inside other proofs. This is too abstract to understand from a description, so here is our example proof for THEOREM TheseHaveSqrt.

THEOREM TheseHaveSqrt ==

ASSUME

NEW X \in {4, 9}

PROVE HasSqrt(X)

PROOF

<1>1 HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9) BY DEF HasSqrt

<1>2 QED BY <1>1

So here, there is one level of proof (level <1>) and 2 steps within the level. Each step in the proof is either a step that requires its own proof, or a step that requires no proof. Here, both steps require their own proof.

Focusing in on step <1>1:

<1>1 HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9) BY DEF HasSqrt

We are asserting that two facts are true: HasSqrt(4) AND (/\) HasSqrt(9). However, if we were to just say:

<1>1 HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9) OBVIOUS

TLAPS would highlight the step in red.

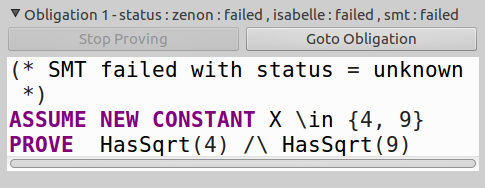

TLAPS does not expand definitions by default. In this case, the back-end provers will see the opaque symbol HasSqrt and have no idea what to do with it. If we check the Interesting Obligations window in the TLA+ Toolbox after trying and failing to prove this step, we see this information:

What this means is that our three backend provers (zenon, Isabelle, and smt) failed to prove our highlighted obligation (<1>1 HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9) OBVIOUS). The information sent to the provers was:

(* SMT failed with status = unknown *)

ASSUME NEW CONSTANT X \in {4, 9}

PROVE HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9)

This is an extremely important tool. We can now tell that the backend provers see the operator HasSqrt but not the definition behind it. If we were to correct our <1>1 step to:

<1>1 HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9) BY DEF HasSqrt

We would be asking TLAPS to use the expanded definition of HasSqrt, and the information sent to our provers would essentially be:

ASSUME NEW CONSTANT X \in {4, 9}

PROVE (\E k \in 1..4 : k * k = 4) /\ (\E k_1 \in 1..9 : k * k = 9)

We wouldn’t see this: the Interesting Obligations window doesn’t show up when something has been successfully proven. This does illustrate the mechanism used by TLAPS to keep the number of facts low: only those that are specifically said to be needed are used for a step. Let’s look at our theorem and proof again:

THEOREM TheseHaveSqrt ==

ASSUME

NEW X \in {4, 9}

PROVE HasSqrt(X)

PROOF

<1>1 HasSqrt(4) /\ HasSqrt(9) BY DEF HasSqrt

<1>2 QED BY <1>1

Every structured proof ends with a QED step, which basically brings together all the proof steps in the rest of the structured proof with the goal of proving the current theorem. In our case, saying

<1>2 QED BY <1>1

Is saying that “We can prove the goal HasSqrt(X) for X in {4, 9} by adding the fact <1>1” into the proof. The QED step itself requires proof (therefore QED OBVIOUS is a possible step), in this case, we’re saying “Assuming <1>1 is true, we have proved the theorem”. Given the wrong facts to QED will cause this step to fail, for e.g. QED BY X = 5 in this case. Once we correct everything, we get:

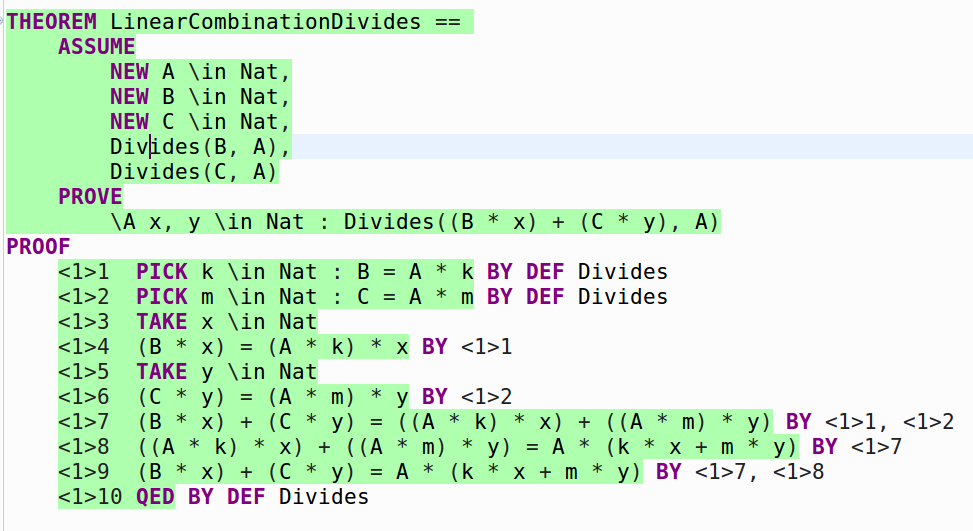

7. Dividing Linear Combinations

We want to prove an interesting theorem:

If:

- A divides B without remainder, and

- A divides C without remainder

Then:

- A divides Bx + Cy (the “linear combination” of B and C) without remainder, where x and y are any two integers.

First we need to define what it means for some value to divide another. We will define it as:

Divides(n, d) == d > 0 /\ \E k \in Nat : n = d * k

So for d to divide some n, d must be more than 0, and there must be a number k such that d * k = n. We could also define it as n % d = 0, but this seems harder to work with: we’d have to prove of d > 0 and so on.

Let’s state the theorem as specified:

THEOREM LinearCombinationDivides ==

ASSUME

NEW A \in Nat,

NEW B \in Nat,

NEW C \in Nat,

Divides(B, A),

Divides(C, A)

PROVE

\A x, y \in Nat : Divides((B * x) + (C * y), A)

This will require a longer structured proof. Simply put: PROOF OBVIOUS fails here, citing insufficient facts. One possible proof is:

THEOREM LinearCombinationDivides ==

ASSUME

NEW A \in Nat,

NEW B \in Nat,

NEW C \in Nat,

Divides(B, A),

Divides(C, A)

PROVE

\A x, y \in Nat : Divides((B * x) + (C * y), A)

PROOF

<1>1 PICK k \in Nat : B = A * k BY DEF Divides

<1>2 PICK m \in Nat : C = A * m BY DEF Divides

<1>3 TAKE x \in Nat

<1>4 (B * x) = (A * k) * x BY <1>1

<1>5 TAKE y \in Nat

<1>6 (C * y) = (A * m) * y BY <1>2

<1>7 (B * x) + (C * y) = ((A * k) * x) + ((A * m) * y) BY <1>1, <1>2

<1>8 ((A * k) * x) + ((A * m) * y) = A * (k * x + m * y) BY <1>7

<1>9 (B * x) + (C * y) = A * (k * x + m * y) BY <1>7, <1>8

<1>10 QED BY <1>9 DEF Divides

There are a lot of new concepts, and we will explore them step-wise.

<1>1 PICK k \in Nat : B = A * k BY DEF Divides

Step <1>1 states that for the rest of the proof, we are going to PICK a value k such that B = A * k, and we state that the reason we can do this is due to the definition of Divides. This makes sense: we said Divides(B, A) which implies B = A * k. Why didn’t we say <1>1 \E k \in Nat : B = A * k BY DEF Divides instead (\E vs PICK)? \E k... makes the definition of k local to only that step, PICK makes k accessible to the rest of the proof when we include the step elsewhere. Maybe it can be thought of as a private variable (\E k) vs a public variable (PICK k).

<1>2 PICK m \in Nat : C = A * m BY DEF Divides

Step <1>2 is pretty much identical to step 1, just that we are doing the same thing for C.

<1>3 TAKE x \in Nat

Step <1>3 is the first proof-less structured proof step that we have encountered. This can be thought of as equivalent to “for all y in Nat…”. Note the difference here: TAKE is like for-all and doesn’t require proof, PICK is like there-exists and does require proof.

<1>4 (B * x) = (A * k) * x BY <1>1

In Step <1>4, we say that by adding the step <1>1 (PICK k \in Nat : B = A * k BY DEF Divides) to our list of facts for this step, we can prove that (B * x) = (A * k) * x, which makes sense since we are just expanding the definition of B. We do this for steps <1>5 and <1>6 for C as well.

<1>7 (B * x) + (C * y) = ((A * k) * x) + ((A * m) * y) BY <1>1, <1>2

<1>8 ((A * k) * x) + ((A * m) * y) = A * (k * x + m * y) BY <1>7

<1>9 (B * x) + (C * y) = A * (k * x + m * y) BY <1>7, <1>8

The next three steps are basic arithmetic to achieve the form (B * x) + (C * y) = A * (some natural number). After this, only one last step is necessary to complete the proof:

<1>10 QED BY <1>9 DEF Divides

So using fact <1>9, we are able to finally prove our theorem.

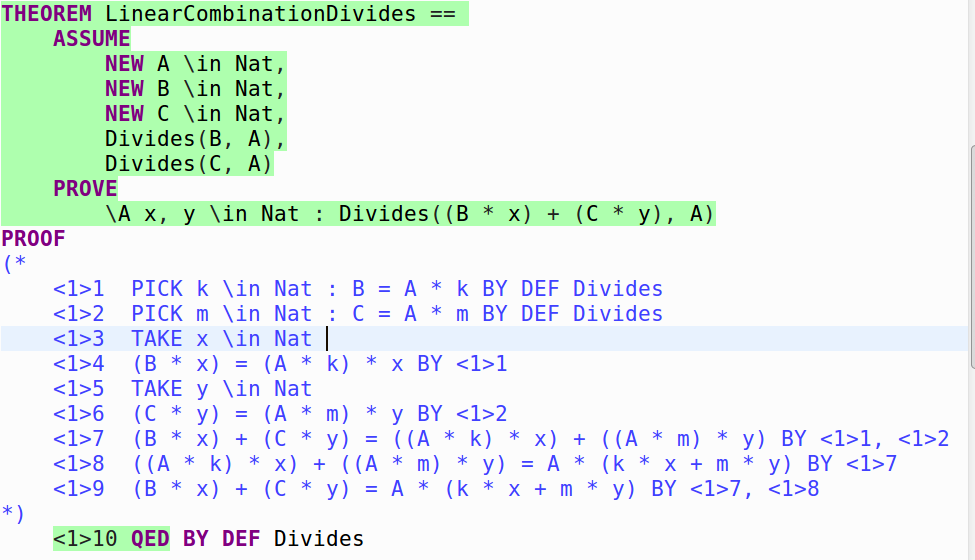

7.1. Not following my own advice

While this example shows the methodical steps behind structured proofs and how to refer to previous steps to prove the current step, TLAPS was actually much smarter than I gave it credit for. I noticed that some steps of my proof were redundant when commenting them out, and then after I removed all of them…

So actually, supplying the definition of Divides to TLAPS was sufficient for the backend provers to prove this theorem. My original definition of Divides had an extra d <= n constraint that I removed while doing some other proofs, since it was an unnecessary constraint, and that was one of the things that made this proof obvious to TLAPS. The lesson to learn here: always check the OBVIOUS and BY DEF <..relevant definitions..> proofs first before trying to prove anything else.

8. Conclusions

TLAPS is a really useful proof system that forces users to write rigorous mathematical proofs. After a while, it mostly feels like working together with the proof system to achieve some goal, as opposed to struggling to teach it some obvious fact. The main window into what the proof system is “thinking” is the Interesting Obligations window when it can’t prove something. I intend to combine my models in standard TLA+/PlusCal/TLC with TLAPS, since we are just scratching the surface of the proof system in this post. It’s also capable of checking temporal logic to a degree, and can handle induction over the natural numbers, among many other capabilities.

To continue learning TLAPS, the resources on TLAPS from my initial post on Learning TLA+ were my main references. I’m not reproducing those references here, in order to limit any updates to the list to just that post. I’d recommend reading through those resources multiple times in different orders until more of TLAPS begins to make sense.